Labour and Anti-Semitism: Balancing the Debate

Entering the debate on Labour and anti-Semitism is always a fraught task. For obvious reasons, the debate is emotionally charged, with people often taking one of two inflexible positions. First, there are those who claim that Labour, since Corbyn’s leadership, and Corbyn himself, is anti-Semitic and anyone who denies this, or partially attempts to nuance the charge, are themselves complicit in anti-Semitism. Second, there are those who claim that most, if not all, arguments that Labour and Corbyn is anti-Semitic are lies – attempts to smear the Labour party and Corbyn to prevent Labour from attaining power. There is, however, a third position – situated in the middle of these two opposing camps. This group does not get a good hearing in the media, but – as is often the case with polarising debates – this middle camp usually has the most balanced perspective on the whole discussion. People of this third group claim that while there is small but consistent evidence of anti-Semitism within the Labour party, proof of Corbyn being ignorant about anti-Semitism, and examples of Labour being slow and hapless when dealing with anti-Semitic complaints, a hermeneutics of suspicion should nonetheless be applied to some of those making these claims.

I would include myself amongst this third group. I do so not only because, as I have suggested, this group holds the most balanced interpretation of events, but because this third position is the only standpoint which can detoxify this whole discourse and deal with the issues raised. To tackle a problem, one first must understand it. Those who block up their ears and shout that Corbyn is a ‘fucking racist’ and who reference anti-Semitism to justify setting up a new political party - which is more concerned with protecting professional class interests - are just as bad as those who argue that anyone critically engaging with anti-Semitism within Labour are neoliberal attack dogs. Both these standpoints fail to understand the complexity of what is going on and therefore fail in aiding the desire people have to address real concerns and acknowledge the rights and wants of the Jewish community within the Labour party specifically, and society generally.

I would include myself amongst this third group. I do so not only because, as I have suggested, this group holds the most balanced interpretation of events, but because this third position is the only standpoint which can detoxify this whole discourse and deal with the issues raised. To tackle a problem, one first must understand it. Those who block up their ears and shout that Corbyn is a ‘fucking racist’ and who reference anti-Semitism to justify setting up a new political party - which is more concerned with protecting professional class interests - are just as bad as those who argue that anyone critically engaging with anti-Semitism within Labour are neoliberal attack dogs. Both these standpoints fail to understand the complexity of what is going on and therefore fail in aiding the desire people have to address real concerns and acknowledge the rights and wants of the Jewish community within the Labour party specifically, and society generally.

Unfortunately, however, before a more balanced position can start the work of detoxifying the current discourse and help accurately diagnose and propose solutions to problems identified, it needs to be seen as a valid standpoint by a good number of people within and outside the Labour party; individuals can only start to work together, towards a common goal, if they share, broadly speaking, a similar interpretative framework. Though, presently, this is not the case.

So, instead of writing about what problems Labour are currently experiencing when it comes to anti-Semitism, and what, possibly, could be done about them, I must further deconstruct inflexible positions – demonstrating why they are imbalanced to the point of being inaccurate and, therefore, unhelpful. A lot of work has been done on this front already, and praise here should go to media commentators such as Owen Jones, Geoffrey Alderman, etc. – there is also an excellent chapter in Francis Beckett and Mark Seddon’s book, Jeremy Corbyn and the Strange Rebirth of Labour England, criticising the current nature of the anti-Semitism debate without falling into the trap of denying its existence. However, more needs to be done. In particular, one narrative has been gaining in popularity recently and needs to be challenged.

It is common to see on Twitter the claim – often, but not exclusively, made by chattering-class, New Labour figures – that Labour before Corbyn was an anti-Semitism free zone. It is, according to this narrative, Corbyn, his radical anti-Israeli standpoint, and those who support him, which has turned the Labour party into a racist swamp which is in desperate need of draining and which, moreover, makes the Labour party unrecognisable from its New Labour days.

A prominent supporter of this narrative is Alastair Campbell. Campbell has, rightly, often expressed disgust at Labour’s tackling of anti-Semitism within its ranks, and has cited it as a reason why he has seriously considered leaving the Labour party – of course, this decision was made for him after he voted for the Liberal Democrats at the European elections. Though, Campbell, being Tony Blair’s spokesman during most of his time as Labour leader is a strong authority to turn to regarding the question of whether Labour has taken a turn for the worse, concerning anti-Semitism, since Corbyn’s election to the leadership.

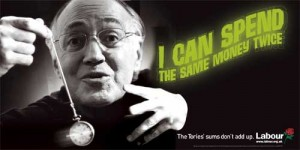

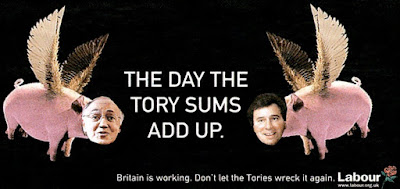

Volume five of Campbell’s well-known diaries covers the 2005 general election when Tony Blair and Gordon Brown faced off against Michael Howard and Oliver Letwin – both Jewish. For the campaign, among other things, Campbell helped produce two posters. The first saw Michael Howard and Oliver Letwin depicted as flying pigs; the second depicted Michael Howard as Fagin. These posters, it should not be a surprise to learn, were interpreted as anti-Semitic by members of the Jewish community as well as Jewish Labour MPs. But, of course, we know that Campbell is a passionate anti-racist campaigner and we know, also, that New Labour, unlike Corbyn’s Labour, was a safe place for Jewish people whose complaints would be dealt with swiftly and sensitivity. We would expect, in other words, that Campbell accepted that the posters could be legitimately interpreted as anti-Semitic, that he apologised, and that he ensured that nothing like this would happen in the future.

Instead, Campbell and those around him agreed ‘to keep firm’, dismissing the suggestion the posters could be offensive. Indeed, Campbell thought it would be funny to retort to the growing outrage with the question, ‘Which animals are they then?’. His diary records how he lamented when one advertising executive – Trevor Beattie – working for New Labour – ‘bought the line that it [the pig poster] was anti-Semitic’ – suggesting that such a capitulation was ‘ridiculous.’ Moreover, the Fagin poster was produced after the flying pig poster, showing that Campbell had not learnt from his first mistake, despite being called out.

But what does this mean? It means that instead of Labour recently turning into an anti-Semitic hotspot, Labour has a history of not taking Jewish concerns seriously and being ignorant about the offensiveness of actions and words which can legitimately be construed as anti-Semitic. This is not, however, because Campbell is a ‘fucking racist’ – though people are free to argue otherwise – but because he and the Labour party at the time, like Corbyn and the Labour party today, are situated within a racist society. This hopefully should not come as a shock, but Britain is still a racist country – years of anti-Semitic feeling and propaganda, colonialism and slavery have left legacies which continue to negatively influence people’s attitudes and beliefs, even if individuals do not explicitly see themselves as racists.

But what does this mean? It means that instead of Labour recently turning into an anti-Semitic hotspot, Labour has a history of not taking Jewish concerns seriously and being ignorant about the offensiveness of actions and words which can legitimately be construed as anti-Semitic. This is not, however, because Campbell is a ‘fucking racist’ – though people are free to argue otherwise – but because he and the Labour party at the time, like Corbyn and the Labour party today, are situated within a racist society. This hopefully should not come as a shock, but Britain is still a racist country – years of anti-Semitic feeling and propaganda, colonialism and slavery have left legacies which continue to negatively influence people’s attitudes and beliefs, even if individuals do not explicitly see themselves as racists. By pointing this out, I do not mean to excuse Labour’s current dealings with anti-Semitism. Yes, Labour exists within a racist society, but Labour’s goal is to create a country free from inequalities and that, of course, includes racial inequalities. Labour, therefore, should be setting the best possible example; not imitating the worse aspects of society. But context is essential, and if we aim to attain a comprehensive understanding of anti-Semitism within the Labour party and what we can do about it, this context needs to be kept in mind. And this is what is so dangerous about the ‘anti-Semitism only started with Corbyn’ narrative; it ignores the roots of anti-Semitism and shifts the blame away from those who are equally responsible. It, moreover, creates a toxic discourse where the main aim seems to be character-assassination and not problem-solving. I firmly believe that many people who adopt these harmful narratives do so with the best of intentions, but they are precisely that: harmful.

It could, of course, be said that while anti-Semitism existed in the days of New Labour, it is far worse now. However, bearing in mind that the Labour membership has expanded dramatically since the New Labour days, and not denying that there is consistent evidence of anti-Semitism within the current Labour party, there is not enough evidence to suggest that what is happening today is of a different nature to what has happened in the past. Having said this, there are instances where anti-Semitism is worse and these cases need to be understood at a micro level to appreciate what is occurring; the point, however, is that making generalised arguments from these cases would not be helpful. In addition, one also must remember that, rightly, the level of awareness concerning anti-Semitism within Labour is greater now than it was during the New Labour days. Objects of interest only present themselves because of the interests of social actors – anti-Semitism is currently a priority interest. Moreover, social media can often be a megaphone for those who hold appalling views – views which would not have been as easily voiced in the past. Overall, therefore, it is not surprising that consistent examples of anti-Semitism are being found. Again, this does not excuse what is happening but explains what might otherwise appear as a disparity.

If we are to move the debate forward positively, then, we need a more balanced approach – one that considers history, intentions, problems with definitions, and different levels of awareness. Some will never change; people will continue to claim that Corbyn is inherently racist and harbours evil intentions, despite evidence to the contrary, and others will believe conspiracy theories that all evidence of anti-Semitism within Labour are false. Others can, however, be convinced to soften their views. And this needs to happen if we are to eradicate the virus of anti-Semitism and make Labour, and society more broadly, acknowledge the contributions, rights and wants of the Jewish community.

Jack Lewis Graham

I set out to read this with the presumption that it would be a long list of tired and well worn defences of the indefensible. Having reached the end, I have to conclude that instead, it is a well-argued and reasoned case for that principle that seems to have been lost from much of our polarised political discourse: the principle of taking a second look.

ReplyDelete